Gold fever

Where does gold come from?

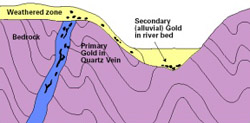

Gold is widely dispersed in the earth’s crust, but only rarely in high enough concentrations to make mining worthwhile. In some places though, heated subterranean fluids have dissolved the scattered gold and redeposited it in more solid, concentrated form. These are called primary gold deposits.

Gold is widely dispersed in the earth’s crust, but only rarely in high enough concentrations to make mining worthwhile. In some places though, heated subterranean fluids have dissolved the scattered gold and redeposited it in more solid, concentrated form. These are called primary gold deposits.

In Victoria, most primary gold is found in quartz veins or reefs, deposited in cracks that opened up during the faulting and folding of Palaeozoic sandstone and mudstone beds, between 440 and 360 million years ago.

Over the course of time, some primary gold deposits have been exposed at the earth’s surface. Aeons of weathering has worn them down and redeposited the gold in the soil and creek beds as secondary (alluvial) gold deposits. Gold nuggets are formed in this way.

More than 2.5 million kilograms of gold has been mined in Victoria, almost half of it from reefs, the remainder from alluvial deposits.

More than 2.5 million kilograms of gold has been mined in Victoria, almost half of it from reefs, the remainder from alluvial deposits.

Snapshots of Victoria's gold mining history

The gold licence system, introduced in 1852, was abolished as a result of a miners rebellion at the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat in 1854. Miners Rights, issued annually, were introduced in 1855.

The gold licence system, introduced in 1852, was abolished as a result of a miners rebellion at the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat in 1854. Miners Rights, issued annually, were introduced in 1855.

This plan, by Ballarat mining surveyor Thomas Cowan, had an unusual purpose: to illustrate, with chilling clarity, the aftermath of a boiler explosion at the East India Company’s mine in October 1861.

This plan, by Ballarat mining surveyor Thomas Cowan, had an unusual purpose: to illustrate, with chilling clarity, the aftermath of a boiler explosion at the East India Company’s mine in October 1861.

The details shown on Cowan’s plan bear out the Ballarat Star’s report of the accident:

'David Campbell, who was last seen alive near the boiler, was thrown a distance of 275 feet [84 metres], and was propelled through the air like a shuttlecock... A man named John Collins and a boy about 19 years of age, named Arthur Henry Stamers, were also blown a considerable distance, and killed instantaneously.'

The boiler was carried away a distance of 162 feet [50 metres], and turned a complete somersault when one of the ends of it touched the ground. Timber, bricks, shingles, and firewood were thrown about in all directions… A stone or piece of brick was hurled some three hundred yards to a Chinaman’s claim, where it struck the horse in the puddling machine and knocked out one of its eyes."

This plan of a mine at Fryers Creek reveals an unusually well developed knowledge of geology for a mining surveyor at the time. No doubt this reflects Richard Kitto’s experience as a miner, not just in Victoria but in the copper mines of Cornwall, where his family had worked for generations.

This plan of a mine at Fryers Creek reveals an unusually well developed knowledge of geology for a mining surveyor at the time. No doubt this reflects Richard Kitto’s experience as a miner, not just in Victoria but in the copper mines of Cornwall, where his family had worked for generations.

Kitto’s careful drafting is evident in details like the timber-lined shaft and windlass.

These hand-coloured plans and cross-sections by Thomas Cowan, mining surveyor, present a three-dimensional view of a mine on the Ballarat goldfield.

These hand-coloured plans and cross-sections by Thomas Cowan, mining surveyor, present a three-dimensional view of a mine on the Ballarat goldfield.

Maps like this not only acted as a record of where gold had and had not been found, but gave an indication of where gold might be found. The fairly crude geological details would have been based on Cowan’s observations in the Enterprise Co.’s mine.

This cross-section by Sandhurst (Bendigo) mining surveyor, Edward Harper, shows how, by 1860, miners were successfully pursuing gold at greater depths.

This cross-section by Sandhurst (Bendigo) mining surveyor, Edward Harper, shows how, by 1860, miners were successfully pursuing gold at greater depths.

By pumping water from its shaft, the Endeavour Co. was able to prospect and mine for gold at 235 feet (70 metres) below the original water-level.

It was on this same line of reef that German-born miner Christopher Ballerstedt had pioneered deep mining in the 1850s. By following the reef’s slope downward, he had disproved the accepted theory that payable gold would not be found at depth.

No less an authority than Sir Roderick Murchison - then the world’s foremost geologist - doubted that payable gold would be found below water level in Victoria.

No less an authority than Sir Roderick Murchison - then the world’s foremost geologist - doubted that payable gold would be found below water level in Victoria.

‘The mass of the public in Victoria,’ Murchison wrote in a letter published by the Bendigo Advertiser, ‘will gladly believe that auriferous treasures really extend from the surface to such vast depths in the solid interior of the earth.… But,’ he cautioned, ‘such a result [would] be at variance with dear-bought experience in many other countries’.

An 1857 Royal Commission into the progress of the Victorian goldfields supported Murchison’s view that mining of the Bendigo quartz reefs would be shallow and shortlived. Miners on (and under) the ground, however, were disdainful of the views dispensed by scientific mining men on the other side of the world. They were sinking ever deeper and still finding abundant gold.

Ferdinand Krausé was one of three geologists employed by the Geological Survey under Brough Smyth in the 1870s.

Ferdinand Krausé was one of three geologists employed by the Geological Survey under Brough Smyth in the 1870s.

In his annual report for 1874, Brough Smyth voiced some displeasure at Krausé’s progress on this map:

'Mr Krausé will not, however, close his labors at Ararat until he shall have made certain sketchmaps and sections necessary for the proper elucidation of some of the geological features shown on the map.'

The finished map showcases not only fine geological mapping, but a painstaking printing process.

Even so, mistakes did happen. In the script along the lower margin, the engraver mirrored the accent in the geologist’s name as è instead of é.

![]() Thomas Brown was still the government mining surveyor at Castlemaine in 1890, more than 30 years after producing his first plan of Wattle Gully.

Thomas Brown was still the government mining surveyor at Castlemaine in 1890, more than 30 years after producing his first plan of Wattle Gully.

This cross-section of workings on Phillips Reef was drawn after the closure of the Forest Creek Wattle Gully Co. mine in 1889, as a record of why the mine had failed - on the shaft’s bottom level the reef had petered out.

Future miners would rely on plans like this one, to determine which ground had already been tried, which had failed, and which might still hold promise.

E.J. Dunn was one of the first generation of Australian-educated geologists, having studied under George Ulrich at Melbourne University.

E.J. Dunn was one of the first generation of Australian-educated geologists, having studied under George Ulrich at Melbourne University.

After his herculean survey of Bendigo, Dunn went on to serve as Director of the Geological Survey and, in 1905, was awarded the Geological Society of London’s prestigous Murchison medal.

This plan by GSV geologist E.J. Dunn illustrates the repetition at depth of the distinctive boomerang-shaped masses of quartz known as saddle reefs. Early miners at Bendigo discovered that a saddle reef at the surface indicated another such reef at depth. It was this predictability that led to successful deep sinking on the Bendigo goldfield.

This plan by GSV geologist E.J. Dunn illustrates the repetition at depth of the distinctive boomerang-shaped masses of quartz known as saddle reefs. Early miners at Bendigo discovered that a saddle reef at the surface indicated another such reef at depth. It was this predictability that led to successful deep sinking on the Bendigo goldfield.

When gold mining faltered with the onset of the 1890s depression, the GSV launched an extensive underground mapping program to gauge the future prospects for mining at Bendigo. The findings of E.J. Dunn and his team were lauded by Bendigo miners and the press:

'The general opinion for many years has been that the Bendigo goldfield is practically inexhaustible. That was the opinion of experienced miners. And now after careful survey and a collation of facts, a scientific opinion is given, which bears this out to the very letter… Mr Dunn expresses the firm opinion that…vast deposits of gold remain to be won compared with which the gold hitherto yielded by the field is trifling. (Bendigo Advertiser, 1892)'

Nor could the Advertiser resist from adding - ‘It is a pity Sir Roderick Murchison is not alive to read these eloquent facts.’ Gold in abundance continues to be found in the reefs more than a kilometre under Bendigo up to the present day.

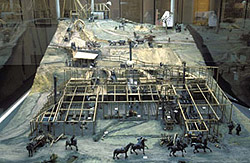

This model depicts the mine and crushing works of the Port Phillip & Colonial Gold Mining Company at Clunes, one of Australia’s most famous mines and a pioneer of large-scale mechanised quartz mining.

This model depicts the mine and crushing works of the Port Phillip & Colonial Gold Mining Company at Clunes, one of Australia’s most famous mines and a pioneer of large-scale mechanised quartz mining.

Floated in London at the end of 1851, the Port Phillip & Colonial Gold Mining Company was the first foreign-owned public company to invest in Victorian gold mining. It was also one of the first Victorian mining companies to employ both professional geologists and metallurgists. Together with the Bendigo goldmines, the Port Phillip Company helped to dispel Murchison’s theory that payable gold would not be found at depth.

The company’s influence spread far beyond Clunes with mining engineers from around the world visiting the mine to study the underground workings and treatment methods. By the mid-1860s, hundreds of Victorian mining companies from Ballarat to Omeo had built crushing plants based on the ‘improved Clunes model’.

The Port Phillip mine remained in operation until 1893, producing 514,886 ounces (15.96 tonnes) of gold, worth $A270 million at today’s prices, from 1.3 million tonnes of quartz ore, with the main shaft reaching 427 metres in depth.

This was the last and most ambitious of ten scale models commissioned from the Swedish-born miner and artisan Carl Nordström, by Professor Fredrick McCoy, founder of the National Museum of Victoria. It took over six-months to complete and cost £215, over twice Nordström’s original quote.

This was the last and most ambitious of ten scale models commissioned from the Swedish-born miner and artisan Carl Nordström, by Professor Fredrick McCoy, founder of the National Museum of Victoria. It took over six-months to complete and cost £215, over twice Nordström’s original quote.

Like all Nordström’s models, it was built ‘on location’ at the mine site in Clunes, using materials readily to hand such as plaster of Paris, hessian, wire, candle wax, sheet lead and timber from packing crates. Nordström took care to make each figure and piece of machinery in exact proportion to its actual size at a scale of 3/8-inch to 1-foot (1 in 32) while cleverly reducing the overall size of the model by shortening the relative distance between various features on the site. The model shows only the first 54 feet of underground workings, although at the time the mine had already reached 200 feet in depth.

The model was a triumph for Nordström when first exhibited in Melbourne in early 1859 and so impressed a reporter from The Argus that he described it as unsurpassed in ‘the boldness of the design, minuteness of detail, and beauty of execution’.

Looking at the sides of the model, one gets a clear idea of how the Geological Survey’s geologists gained a better understanding of Victoria’s stratigraphy by examining underground mine workings. The quartz reefs (shown in white) run generally north-south, but each dips to the west at a different angle and is intersected by various faults.

More information

- Find out more about gold and other minerals in Victoria.

- History of gold mining in Victoria

Page last updated: 02 Jun 2021