The early years

Selwyn and the birth of the Geologival Survey Victoria (GSV)

Soon after gold was discovered in 1851, Victoria’s Governor La Trobe wrote to the Colonial Office in London, urging ‘the propriety of selecting and appointing as Mineral Surveyor for this Colony a gentleman possessed of the requisite qualifications and acquaintance with geological science and phenomena’.

Soon after gold was discovered in 1851, Victoria’s Governor La Trobe wrote to the Colonial Office in London, urging ‘the propriety of selecting and appointing as Mineral Surveyor for this Colony a gentleman possessed of the requisite qualifications and acquaintance with geological science and phenomena’.

That gentleman was Alfred Selwyn.

Selwyn’s appointment in May 1852, and his subsequent arrival in Melbourne at the end of 1852, heralded the birth of the Geological Survey of Victoria. Working at first with only one assistant and a tentkeeper, he mapped more than 1000 square miles a year.

As the GSV expanded, Selwyn trained and supervised his field geologists – most of them novices – to his own meticulous standards. Energetic, quick-tempered, and a stickler for accuracy and ‘scientific truth’, Selwyn was no easy taskmaster. But the maps and reports produced under his direction were of such a high standard that, by the 1860s, Victoria’s Geological Survey ranked among the best in the world.

Geological map of the area between Malmsbury and Bendigo (1853)

This is Alfred Selwyn’s field sheet (or working copy) of Victoria’s first geological map, completed within three months of his arrival in the colony.

This is Alfred Selwyn’s field sheet (or working copy) of Victoria’s first geological map, completed within three months of his arrival in the colony.

Not surprisingly, Selwyn had commenced the work of the Geological Survey of Victoria by mapping the area encompassing the prodigious goldfields of Bendigo and Castlemaine.

As the basis of his map, Selwyn used Surveyor - General Robert Hoddle’s earlier plan, to which he added geological details and observations.

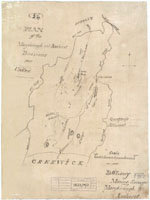

Geological sketch of the country in the vicinity of Mount Alexander (1853)

The finished map, based on Selwyn’s field sheet, is called a ‘geological sketch’, probably to indicate the rapid and preliminary nature of the survey that created it.

The finished map, based on Selwyn’s field sheet, is called a ‘geological sketch’, probably to indicate the rapid and preliminary nature of the survey that created it.

For all his speed, Selwyn had correctly identified the main rock types, recognising the Paleozoic bedrock for its similarity to that in North Wales, where he had formerly worked.

Selwyn has shown the different rock types by a system of colouring, explained in an accompanying key. The colours he chose were not just his personal favourites, but part of a standard code used in all geological maps to indicate the age and type of the rocks depicted.

Geological map of the Yarra River Basin and drainage area of Western Port Bay (1856)

This hand-drawn and -coloured map covering the area around Melbourne was the result of Selwyn’s second geological survey, completed in 1856.

This hand-drawn and -coloured map covering the area around Melbourne was the result of Selwyn’s second geological survey, completed in 1856.

At Keilor, in the top lefthand panel, Selwyn has noted ‘First Graptolites discovered in Australia by C.D.H. Aplin, Geo. Survey of Vic., May 1856’. In time, graptolites - a minute marine fossil - would prove a key to understanding the sequence of Victoria’s geology.

Quarter sheets – the first systematic geological mapping

In 1856, Selwyn and his team commenced a systematic program of surveying – beginning with central Victoria and the country around Melbourne – which would result in the map series known as the quarter sheets.

In 1856, Selwyn and his team commenced a systematic program of surveying – beginning with central Victoria and the country around Melbourne – which would result in the map series known as the quarter sheets.

This was map-making from scratch. Since no reliable topographic maps existed, Selwyn’s geologists had to create their own, precisely surveying every gully and hill before they could overlay the geological details. Of the four years (1858-62) it took Ulrich and Aplin to complete the Castlemaine quarter sheets, three were spent in mapping the topography.

To figure out what lay under the ground, field geologists relied on clues exposed in outcrops, road cuttings, quarries – and mines. In the course of their Castlemaine mapping, Aplin and Ulrich climbed into 3,000 diggers’ holes and dug 81 of their own, each about 3 metres deep. They not only ‘read’ the strata exposed in these holes, but prospected for gold, so as to gauge the extent of the goldfields.

Alfred Selwyn declared the Castlemaine quarter sheets ‘a perfect specimen of what the goldfields’ geological maps ought to be’.

Quarter sheet 9NW Taradale & field compilation sheet (Ulrich, 1859)

One of the four Castlemaine quarter sheets (top), this beautifully lithographed geological map covers the area between Fryerstown, Taradale and Malmsbury.

As well as showing the distribution of alluvial and reef gold, the map features long-gone landmarks such as the ‘Old House at Home’ public house on what is now the Calder Highway.

Ulrich’s original field compilation sheet (bottom) shows the painstaking detail with which he plotted his field observations - not all of which were included on the final map.

Quarter sheet 15NE Guildford (Aplin & Ulrich, 1864)

This map of the area around Guildford (between Castlemaine and Daylesford) includes notes and sketches in the margins as well as on the map itself.

This map of the area around Guildford (between Castlemaine and Daylesford) includes notes and sketches in the margins as well as on the map itself.

Features of interest include the South Muckleford racecourse (top left), Pickpocket diggings (bottom left), and the high basalt terraces, remnants of lava that flowed from a volcano about 3 million years ago.

Note that hills are depicted by feathery, radiating lines rather than the contours commonly used on maps today.

Ulrich & Aplin

The geologists responsible for the Castlemaine quarter sheets were C. D’Oyley Aplin and George Ulrich.

When he joined the GSV in 1856, Aplin was entirely without experience in geological surveying. But, under Selwyn’s supervision, he worked on 26 maps of areas near Melbourne, including Moonee Ponds, Williamstown and St Kilda, before commencing on the Castlemaine quarter sheets in 1858.

A decade later Aplin took his expertise north, as government geologist for southern Queensland.

Ulrich had studied geology in his native Prussia before joining the gold rush to Victoria in 1853. Several years of mixed fortune as a digger added to his geological training to outfit him perfectly as a field geologist with the GSV. He went on to become an authority on the minerals of Australia, and taught at Melbourne University before being appointed Professor of Mining and Mineralogy at the University of Otago, New Zealand, in 1887. He died at 70, following a fall on a rock-collecting expedition.

Quarter sheet 24SE Geelong (Daintree, 1861)

The area around Geelong was geologically important to Victoria in the mid-19th century - not for gold, but as a source of building stone which was in high demand in the decades after the gold rushes.

The area around Geelong was geologically important to Victoria in the mid-19th century - not for gold, but as a source of building stone which was in high demand in the decades after the gold rushes.

Daintree’s map shows numerous basalt and sandstone quarries, together with a scattering of vineyards on the northern slopes of the Barrabool Hills.

The reserve for an orphan asylum at Fyansford gives an insight to the social policies of the time.

Richard Daintree

Richard Daintree came to Australia for the sake of his health in 1852. Two years later, he was Alfred Selwyn’s field assistant in the production of some of Victoria’s earliest geological maps.

Richard Daintree came to Australia for the sake of his health in 1852. Two years later, he was Alfred Selwyn’s field assistant in the production of some of Victoria’s earliest geological maps.

Seriously drawn to a career in geology, Daintree returned to London in 1856 to study assaying, and also acquired a knowledge of photography. Back in Melbourne in 1858, he was appointed field geologist with the GSV.

Daintree surveyed Victoria’s coal deposits and mapped the geology of the Bellarine Peninsula. Complementing his geological fieldwork were photographs recording mine workings, rock formations, scenic views, and even fossils. In fact, it is as a photographer that Daintree is best remembered in Victoria.

Leaving the GSV in 1864, he was appointed government geologist for northern Queensland, where the Daintree National Park bears his name.

Quarter sheets 1NW, NE, SW & SE (c.1858)

The Geological Survey of Victoria’s first four quarter sheets, covering the Melbourne metropolitan area, were complete by 1858. Here, they are presented as a single map.

The Geological Survey of Victoria’s first four quarter sheets, covering the Melbourne metropolitan area, were complete by 1858. Here, they are presented as a single map.

Aplin and his field assistants would have gleaned their geological data by grubbing around the city and suburbs, examining road cuttings, river embankments and building sites. Their findings were then overlaid on Survey Department maps of the area to produce the geological quarter sheets.

Many of the map’s features will be familiar to today’s Melburnians; some prominent landmarks, however - like Batman’s Hill and the West Melbourne swamp - have since dropped from view.

Map printing

Limestone printing blocks were used for lithographic printing of the quarter sheet map series.

Limestone printing blocks were used for lithographic printing of the quarter sheet map series.

The first stage of the printing followed the process of copper plate engraving. Fine linework and text were engraved in reverse onto copper plates, which were then inked and pressed against lithographic transfer paper. By means of pressing, the image was next transferred from the paper onto a limestone printing block.

Now hills and other features were added by hand to the image on the flat stone surface, to which paper was then applied and pressed to produce a printed map. Colour prints required multiple limestone blocks bearing the same image, one block for each colour.

The GSV’s first quarter sheets were colour-printed in 1859 using a hand press, each sheet passing through the press once for each colour. The introduction of a steam-powered press soon made map production faster and cheaper.

Photography was incorporated into the process during the early 20th century and until recently most maps were printed by lithography, using metal plates. With the introduction of high-quality digital plotters during the last decade, the GSV has moved to on-demand plotting of geological maps.

Selwyn versus Brough Smyth: Geologists versus mining surveyors to map goldfields

In its formative years, the Geological Survey of Victoria was pulled between the competing demands of scientific rigour and the mining industry.

Gold mining occupied centre-stage in Victoria at that time, and the GSV was subject to constant scrutiny -

The labours of the field geologists have resulted in a series (very far from complete) of beautiful maps. These undoubtedly are a credit to the colony, but can anybody say that up to this time they have done anything to assist the miner, except in the most general way, to new fields of labour? Mr Selwyn, we have no doubt, is a theoretical geologist of the highest class, but… (The Age, 23 July 1866)

Also critical of Selwyn’s steady, scientific approach was Robert Brough Smyth, Secretary of the Department of Mines. In 1859, Smyth had appointed a government mining surveyor to each Victorian goldfield. As well as regulating and reporting on local mining activity, these surveyors from time to time produced maps to show the state of mining in their area. Smyth believed that his men - observant and on-the-spot, but largely untrained - were better equipped than Selwyn’s geologists to produce maps and reports of practical use to miners.

For years, Smyth and Selwyn tussled for control of the Geological Survey, and in 1869 Smyth won. In the name of cost-cutting, the government disbanded the GSV and the embittered Selwyn took up a post in Canada. A year later, the GSV was revived under Smyth’s superintendence.

Plan of Maryborough and Amherst Division (1859)

This poorly drafted, misspelt, and largely unlabelled map - the work of Maryborough mining surveyor, Denis O’Leary - shows the rough position of quartz reefs and alluvial leads in the Amherst area.

This poorly drafted, misspelt, and largely unlabelled map - the work of Maryborough mining surveyor, Denis O’Leary - shows the rough position of quartz reefs and alluvial leads in the Amherst area.

Maps like this lent strength to Alfred Selwyn’s argument that this kind of mapping should only be carried out by trained geologists. No doubt Brough Smyth would have countered that O’Leary’s rough map served the immediate needs of miners on the Amherst goldfield.

Plan of Golden Point section of Forest Creek (1859)

This section of a larger map of the Castlemaine area shows the location of mining leases at Golden Point, south of Chewton.

This section of a larger map of the Castlemaine area shows the location of mining leases at Golden Point, south of Chewton.

It was the discovery of gold at Golden Point in October 1851 which triggered the rush to the fabulously rich Mount Alexander goldfield.

By 1859, many individual miners had grouped into companies and held leases over large areas of gold-bearing ground. Notice the concentration of Welsh names - Evans, Davis, Thomas, the Glamorganshire Co - on the left-hand side of this map. Today this area is marked by the tumbled stone ruins of a mining settlement known locally as the Welsh Village.

Claims leased by Chinese diggers and gardeners follow the course of Forest Creek, with a Chinese camp on the west bank.

Plan of Wattle Gully, Chewton (1859)

This map of the Wattle Gully area was hand-drawn by Thomas Brown, the Department of Mines’ Castlemaine mining surveyor.

This map of the Wattle Gully area was hand-drawn by Thomas Brown, the Department of Mines’ Castlemaine mining surveyor.

Apart from the position of goldbearing quartz reefs, Brown’s map contains no geological information, and its usefulness is limited by the absence of a key. It does, however, show features like puddling machines, buildings, and Chinese camps (top left & right).

Puddling machines

Puddling machines were pioneered on the Victorian goldfields in 1854 as an affordable means of processing gold-bearing clay on a large scale.

Puddling machines were pioneered on the Victorian goldfields in 1854 as an affordable means of processing gold-bearing clay on a large scale.

A horse dragged a harrow repeatedly through a circular, barklined trough full of clay and water, ‘puddling’ the mixture into a thin sludge. Any gold freed from the lumpy clay would sink, remaining behind on the bottom of the trough after the watery sludge was drained off. A clean-up of the residue, using tin-dish or cradle, would bring the gold finally to light.

Castlemaine Mining District (1860)

The work of local Mines Department surveyors, this 1860 map was, in effect, a miners’ ‘road map’ to the gold workings in the Castlemaine mining district.

The work of local Mines Department surveyors, this 1860 map was, in effect, a miners’ ‘road map’ to the gold workings in the Castlemaine mining district.

Alluvial (shallow gold-bearing) ground is plainly shown in blue, while reefs are indicated by red lines running north-south. The clarity of these details is somewhat undone, however, by the lack of an explanatory key. By way of consolation, an index to gold-mining localities is included at the foot of the map. Can you find Dirty Dick’s Gully and Murdering Flat?

Plan showing part of New Year’s Flat, the Bald Hill and Vaughan (1862)

New Year’s Flat, south of Fryerstown, was rushed (and named) on New Year’s Day, 1853. A digger who watched the swarming scene from nearby Bald Hill later called it ‘the most animated sight of those stirring times that I ever witnessed’.

New Year’s Flat, south of Fryerstown, was rushed (and named) on New Year’s Day, 1853. A digger who watched the swarming scene from nearby Bald Hill later called it ‘the most animated sight of those stirring times that I ever witnessed’.

Mining Surveyor Richard Kitto’s map of almost a decade later shows alluvial gold-mining claims and puddling machines flanking Fryers Creek to its junction with the Loddon River at Vaughan.

An area near New Year’s Flat is known locally as Irishtown; the cluster of Irish claimholders thereabouts on Kitto’s map explains why.

Richard Kitto

Richard Kitto left his native Cornwall for Victoria at the height of the gold rushes. After stints at mining and schoolteaching, he was appointed government mining surveyor at Fryers Creek, south of Castlemaine, in 1860.

Richard Kitto left his native Cornwall for Victoria at the height of the gold rushes. After stints at mining and schoolteaching, he was appointed government mining surveyor at Fryers Creek, south of Castlemaine, in 1860.

As mining surveyor, Kitto was well placed to judge the prospects of the district’s gold reefs, and he was involved in several mining companies. After resigning his government position in 1866, Kitto served as a member of parliament and continued in the mining business until his most ambitious venture, the Duke of Cornwall mine, failed in 1875. The towering stone ruins of the mine’s Cornish-style engine house can still be seen near Fryerstown.

Page last updated: 02 Jun 2021