Off the beaten track

Late 19th century exploration in eastern Victoria

During the last decades of the 19th century, government-funded track cutting opened up eastern Victoria to both the mining and timber industries. As a further inducement to development, GSV geologists surveyed and mapped coal and gold deposits in the region.

Between 1873 and 1877, R.A.F. Murray surveyed 3500 square miles (5600 sq km) of southwest Gippsland, including the Walhalla goldfield. Sometimes he was accompanied by government prospecting parties who dug shafts and tunnels to sample a field.

In places where mining was already in progress, geologists carried out detailed underground mapping, as a guide to further mining operations. By working closely with miners and prospectors in an effort to reinvigorate Victoria’s mining industry, the Geological Survey showed itself at its most practical, its least ‘purely’ scientific.

Geological sketch map - portions of Dargo and Bogong (1887)

R.A.F. Murray’s map of the country between Bogong and Dargo shows where gold-bearing deposits ran deep beneath the basalt capping of the high plains.

R.A.F. Murray’s map of the country between Bogong and Dargo shows where gold-bearing deposits ran deep beneath the basalt capping of the high plains.

Miners were guided by Murray’s map in deciding the best spot for shaft-sinking or tunnelling under the basalt in search of gold.

In the course of his survey, Murray may well have been grateful for the meagre comforts offered by Parslow’s Hotel, nestled at the northern foot of Mt Parslow.

Alfred Howitt & R.A.F. Murray

Reginald Murray arrived on the Victorian goldfields as a boy in 1855. The rest of his family returned to England, but he remained behind to find employment as a junior field assistant with the Geological Survey when he was just 16. His first expedition took him into the wild country of the then-unexplored Otways.

Murray worked almost 40 years for the GSV, to become one of the colony’s most experienced geologists.

Alfred Howitt was 22 when he came seeking gold in 1852, and he proved to be a natural bushman. In 1860, he prospected the remote Crooked River goldfield in the Victorian alps, and the following year led the expedition to find Burke and Wills. He served as police magistrate and mining warden to East Gippsland from 1863 until 1889, when he was appointed Secretary of Mines.

A keen natural scientist, during his years in Gippsland (‘in his leisure time’) Howitt won international recognition in the fields of geology and botany and, through his interest in Aboriginal culture, pioneered the study of anthropology in Australia.

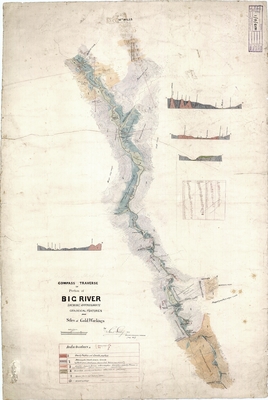

Big River gold workings - geological traverse (1887)

James Stirling produced this hand-drawn and painted map of gold workings in the Big River area, north of Omeo. A handful of miners had been working in the area since the 1860s–their huts are marked on the map–without much success. The purpose of Stirling’s survey was to pinpoint the source of the Big River gold, in the hope of stimulating mining on a larger scale.

James Stirling produced this hand-drawn and painted map of gold workings in the Big River area, north of Omeo. A handful of miners had been working in the area since the 1860s–their huts are marked on the map–without much success. The purpose of Stirling’s survey was to pinpoint the source of the Big River gold, in the hope of stimulating mining on a larger scale.

Stirling also investigated the discovery of tin in Wombat Creek, at the foot of Mt Wills. By 1890, it looked as if Mt Wills would spark a new mineral boom for Victoria; but the tin grades proved so poor that miners soon reverted to gold mining.

In the course of his Big River survey, Stirling and members of a government prospecting party explored an underground cave in the Wombat Creek valley. Here is an excerpt from Stirling’s report of their adventure–

Determined to fully explore this at any risk, young Ralston and myself divested ourselves of all superfluous clothing, and, candle and hammer in hand, proceeded to squeeze ourselves down a very circuitous passage for fully 20 feet, until further exploration seemed impossible. Below us was a narrow hole about 1 foot wide by 14 inches broad, apparently opening to an unknown depth, from which a strong current of cold air was flowing. Having secured a line, by uniting our straps, handkerchiefs, &c., we lowered a candle, and, peering down the narrow orifice, could see a deep chamber about 30 feet below us. We decided to try and enlarge the opening to a dimension sufficient to squeeze down through it, fix a rope on the landing, and descend hand over hand. After some exciting hours we managed, with the assistance of Mr Titu and Ralston, sen., to enlarge the opening sufficient to enable Mr Ralston, jun., to descend. His excited remarks as to the supposed vastness of the chamber he had entered re-acted upon the writer, who, after a severe squeezing, in which his shirt was torn, managed to descend to the first landing in the usual sailor fashion, hand over hand. The difficulty in ascending by the same primitive process never entered the minds of the two explorers.… Our supply of light running short, we decided to return to the surface, and bring a sufficient supply of lights, with pick, &c., to enable us to continue explorations next day. The difficulties experienced in ascending need not be enlarged upon; they can be sufficiently understood. To climb up a rope 30 feet is no mean feat of gymnastics. By knotting the rope we managed to ascend, but the difficulty of squeezing upward through the small hole, which seemed to have decreased in aperture since our descent, was something to be remembered as an episode in cave hunting without parallel in the life of the writer.

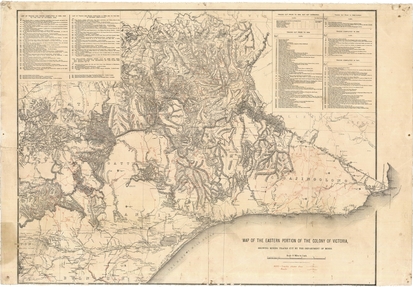

Eastern Victoria, showing mining tracks cut by the Department of Mines (1899)

Between 1894 and 1899, more than 2400 miles (3840 km) of tracks were cut throughout eastern Victoria at the direction of the Department of Mines.

Between 1894 and 1899, more than 2400 miles (3840 km) of tracks were cut throughout eastern Victoria at the direction of the Department of Mines.

Remote areas became more accessible not only to miners and GSV geologists but, eventually, to settlers and tourists. Many of the tracks cut during that period form the basis of today’s road system.

A description of some of the tracks cut during 1899 hints at the hazards encountered by track-cutters–

From Little Bog and Bulda Rivers to Bulda. Up Little Snowy and Digger’s Creeks from Eskdale to the Mount Wills Track. From the Loch Valley-road at Bennett’s Creek to the Starvation-Noojee Track No. 218.Up Bull Paddock Creek.

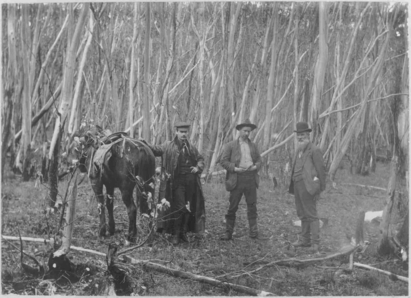

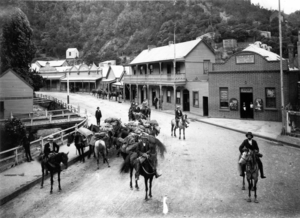

Geological Survey party leaving Walhalla for Mount Baw Baw, January 1904

On horseback at left is William Baragwanath, who published detailed reports on the Ballarat and Walhalla goldfields and would become Director of the Geological Survey in 1920.

On horseback at left is William Baragwanath, who published detailed reports on the Ballarat and Walhalla goldfields and would become Director of the Geological Survey in 1920.

Field mapping in the 19th century

Nineteenth-century geologists were often frustrated by the need to start from scratch, painstakingly mapping an area’s topography before their geological map could be drawn. When C. D’Oyley Aplin was mapping the central Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, he grumbled about the tedium of making topographic maps.

Nineteenth-century geologists were often frustrated by the need to start from scratch, painstakingly mapping an area’s topography before their geological map could be drawn. When C. D’Oyley Aplin was mapping the central Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, he grumbled about the tedium of making topographic maps.

Geologists faced the same problem throughout the 19th century, as most remote areas had been mapped only in the crudest detail. When making a geological map of the goldfields around Walhalla and Woods Point in the 1890s, O.A.L. Whitelaw found himself no better equipped than geologists of forty years earlier.

Just like Selwyn or Aplin, Whitelaw set off into uncharted bush with a team of geologists, assistants and packhorses. His survey equipment was likewise no different from that used by his predecessors: theodolite, compass, chain, aneroid barometer, and an indispensable pencil and notebook. And he had to begin by mapping the topography, without which his geological observations would be worthless.

19th Century Surveying Instruments

GSV geologists in the 19th century had to use a cumbersome theodolite (right) to plot geological observations. The theodolite measures angles and was used for more exacting map-making. Sometimes a line of accurately measured reference points was set up by theodolite then quicker but less accurate survey methods filled in the gaps.

GSV geologists in the 19th century had to use a cumbersome theodolite (right) to plot geological observations. The theodolite measures angles and was used for more exacting map-making. Sometimes a line of accurately measured reference points was set up by theodolite then quicker but less accurate survey methods filled in the gaps.

The distance between points was measured with chains or tapes (below, B - front right). In some cases distance was estimated by triangulation - if one distant but unknown point was observed from two known points, the distance to the unknown point could be computed mathematically. If accuracy was not required then the pacing method was used–geologists simply counted their steps.

The transit compass (right, C - center left) is a less accurate method of map-making. It measures angles like the theodolite but relies on the compass staying true. If the compass were affected by stray magnetic fields, the measured angles and final map may be inaccurate.

The barometer (right, D - front left) is used to measure height above sea level. It was the prime tool for determining height along survey traverses.

The barometer (right, D - front left) is used to measure height above sea level. It was the prime tool for determining height along survey traverses.

The field book (right, E - back left) contains the geologist’s survey observations, drawings and descriptions of rocks. Using this information, together with drawing instruments like the brass protractor (right, F - center), the final map takes shape back in the tent or office.

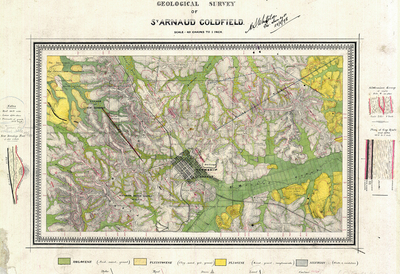

Geological survey of St Arnaud goldfield (1898)

The Department of Mines’ trackcutting program was not confined to eastern Victoria. Tracks were also made through dense, scrubby country in the north of the colony in an effort to extend existing goldfields.

The Department of Mines’ trackcutting program was not confined to eastern Victoria. Tracks were also made through dense, scrubby country in the north of the colony in an effort to extend existing goldfields.

Mining tracks are clearly shown on H.S. Whitelaw’s 1898 map of the St Arnaud goldfield. Renewed mining activity is also evident in the prospecting holes (top left corner), dug by miners seeking the elusive New Bendigo lead.

This hand-drawn map - Whitelaw’s original field sheet - carries a wealth of fine detail, including the outline of a rabbit-proof fence.

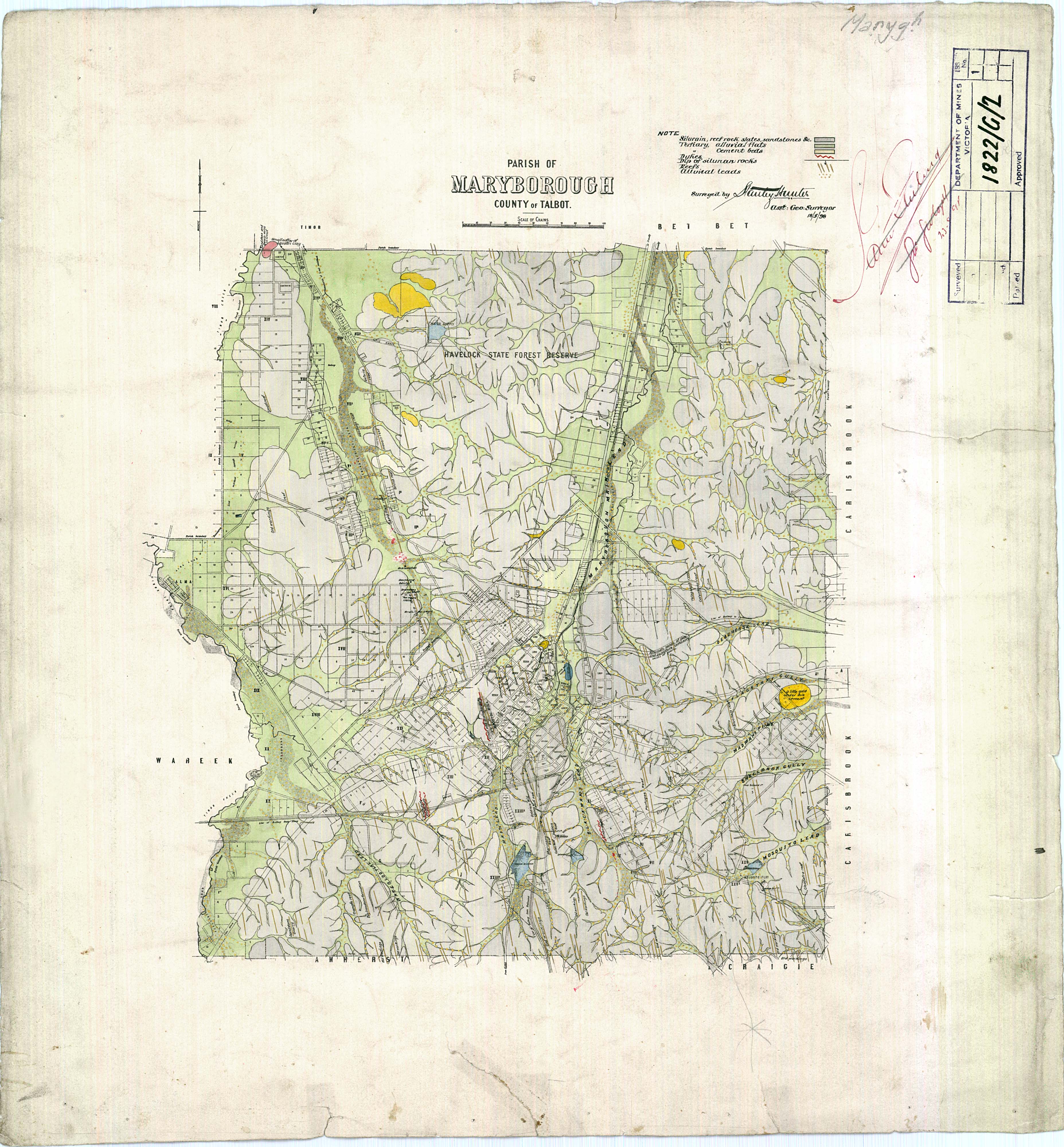

Parish of Maryborough geological plan (1898)

In the 1890s, the Geological Survey commenced a program of parish mapping. This program enabled the rapid extension of geological mapping to areas not covered by the quarter sheets.

In the 1890s, the Geological Survey commenced a program of parish mapping. This program enabled the rapid extension of geological mapping to areas not covered by the quarter sheets.

Stanley Hunter produced this map with relative speed by overlaying geological information on a Survey Department parish plan of Maryborough. Note the unusual detailing in gold ink to indicate areas containing alluvial gold.

Page last updated: 02 Jun 2021