Coal - Powering Victoria

Black coal

As each Australian colony was founded, the discovery of local supplies of coal – the lifeblood of industry – was a priority.

As each Australian colony was founded, the discovery of local supplies of coal – the lifeblood of industry – was a priority.

The earliest report of coal in Victoria came in the 1820s when Hume and Hovell found a seam of black coal at Cape Paterson. But it would be 1852, when Victoria was newly separated from NSW and the gold rushes were at their height, before the government actively sought a local source of coal.

Black coal, with its low moisture content, was regarded as the premier fuel for household heating, industry, and railways. The coal deposits at Cape Paterson were mined from the late 1850s, but never produced anything like enough to make Victoria self-sufficient in black coal.

The search for coal was a priority for the Geological Survey from its inception. Alfred Selwyn discovered black coal at Wonthaggi as early as 1858, but it was of too poor a quality to make mining worthwhile. A thorough survey of black coal deposits of south Gippsland during the 1890s drew no better conclusion about the viability of the resource.

Things changed in 1909 when a long strike by NSW coal miners caused a shortage of black coal in Victoria. Work carried out by the Geological Survey led the government to open the State Coal Mines at Wonthaggi, ensuring Victoria a degree of selfsufficiency in this vital fuel. The State Coal Mines closed in 1968.

Sections to accompany geological quarter sheet No. 3 Kilcunda to Woolamai (1892)

James Stirling was active in mapping the south Gippsland coal deposits during the 1890s.

James Stirling was active in mapping the south Gippsland coal deposits during the 1890s.

Here Stirling’s geological cross-sections of coastal coal deposits are accompanied by scenic watercolour panels. Note the use of seagulls to indicate the position of notable features (e.g., one seagull = San Remo, two seagulls = coal seam), a hallmark of Stirling’s work.

It seems that Stirling’s whimsical style did not appeal to everyone. An anonymous pencilled comment at the top of the sheet reads: ‘This work lies and would only be done by a bombastic skite like Stirling. Lot of work - Little Art.’

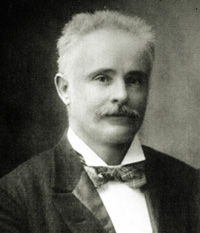

James Stirling

Born in Geelong in 1852, James Stirling spent his youth in East Gippsland. After stints as a mail-rider, stonemason and draughtsman, at the age of 21 he became a Lands Department surveyor at Omeo.

Born in Geelong in 1852, James Stirling spent his youth in East Gippsland. After stints as a mail-rider, stonemason and draughtsman, at the age of 21 he became a Lands Department surveyor at Omeo.

Stirling was interested in everything. A disciple of Darwin, in his spare time he engaged in geological, botanical, ethnographic and meteorological research. From the late 1870s, as a government mining surveyor, he recorded mining activity all over the mountains. On one occasion, reporting an alleged gold discovery, he wrote: I proceeded over the Australian Alps to the locality indicated, having been compelled to swim the Mitta Mitta at Hinnomunjie crossing en route.

Another time, he investigated a supposed ‘fossil canoe’ unearthed in gold workings near Omeo. ‘The geological objections to the possibility of its being a canoe fashioned by human skill are numerous,’ wrote Stirling; ‘[but]…even if Mr Saul Morris has not discovered a canoe, he has set others searching for other relics in these drifts, which may result in adding to the sum total of our scientific knowledge.’

Stirling joined the Geological Survey in 1887, and rose to Government Geologist ten years later.

Brown coal

Raw brown coal, containing up to 70 per cent moisture, has long been regarded as inferior to black coal as a fuel. Nonetheless, brown coal was discovered in Victoria in the 1860s and, in the absence of a major black coal resource, was mined near Morwell from 1887.

Raw brown coal, containing up to 70 per cent moisture, has long been regarded as inferior to black coal as a fuel. Nonetheless, brown coal was discovered in Victoria in the 1860s and, in the absence of a major black coal resource, was mined near Morwell from 1887.

The Great Morwell Coal Mining Company made the first Victorian briquettes in 1892, using a process that dried and compressed raw brown coal. However, technical difficulties, competition from imported black coal and a bushfire closed the mine in 1899.

During the early years of the 20th century, the Geological Survey was instrumental in developing large-scale exploitation of Victoria’s brown coal reserves.

In 1917, Dr Hyman Herman, Director of the Geological Survey, supervised the reopening of the Great Morwell Brown Coal Mine to provide emergency fuel during a NSW coal miners strike. This action led to the formation of the State Electricity Commission (SEC), which Herman joined as Engineer-in-Charge of Briquetting & Research.

The SEC opened up major brown coal mines in the La Trobe Valley during the 1920s, to meet the increasing demand for electricity. Today, raw brown coal remains Victoria’s main source of heat energy for electrical power generation, while briquettes are also produced for industrial and domestic fuel.

Briquette press model (1900)

Following the formation of the Electricity Commissioners (later the SECV) in 1919, technical information on up-to-date methods of brown coal mining and briquette-making was sought from Germany. The Rhineland, where the main mines were located, was occupied by British forces at this time, but the mines were owned by private syndicates that jealously guarded their technical knowledge.

In a clandestine operation directed by Sir John Monash (later SECV Chairman) and led by Major Noel Mulligan, a small contingent managed to gain the confidence of technical staff at the Fortuna mine. Over a period of three months plans, photographs and other technical information including this small model were obtained by ‘special methods’.

The scale model depicts a steam operated briquette press of the type used by German mines from about 1900. Eight presses similar to this formed the first plant installed at the Yallourn Briquette Factory in 1924.

After crushing and drying to remove three-quarters of its moisture, brown coal was fed into the conical hopper and compressed at high pressure. The resulting briquettes provided a compact high-energy fuel that could be easily transported and handled and burnt in conventional boilers and furnaces designed for black coal.

Experimental briquettes

Following the failure of the Great Morwell Coal Mining Company, the Geological Survey of Victoria took an active interest in solving the technical problems of making briquettes from Victorian coal.

In 1901, James Stirling visited Germany to study briquette-making methods. A series of experiments followed, which led to the production of sample briquettes made from Wonthaggi black coal (A - back left) and Morwell brown coal (B - back right) in 1910.

Stirling’s successor, Hyman Herman, made the first briquettes from Morwell brown coal without a binding medium in 1918. This experimental briquette (C - front) was made in a small laboratory in Fitzroy using equipment borrowed from Melbourne University.

Herman later published several works on the use of brown coal and directed construction of the SECV’s first briquette plant at Yallourn.

Kilcunda coalfields, Parish of Woolamai (1893)

James Stirling’s map shows the original discovery site of Kilcunda black coal seam in coastal cliffs to the west of Kilcunda.

James Stirling’s map shows the original discovery site of Kilcunda black coal seam in coastal cliffs to the west of Kilcunda.

The tramway shown in this plan, constructed by the Western Port Coal Company in the early 1870s, ran from the mines at Kilcunda to a wharf at San Remo. Coal was loaded onto boats at the wharf for shipment to Melbourne.

Geological map of the North Korumburra Coal Company’s lease (1893)

In typically flamboyant fashion, James Stirling has ‘framed’ his map with scenic cross-sections. His experimentation with artistic lettering renders the scale and labelling almost illegible in places - but beautiful, nonetheless.

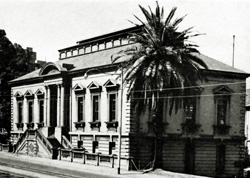

The Geological Museum

In recognition of the Geological Survey’s role in opening up the Wonthaggi coalfield in 1909, the Victorian government built a Geological Museum in Macarthur Street, East Melbourne.

In recognition of the Geological Survey’s role in opening up the Wonthaggi coalfield in 1909, the Victorian government built a Geological Museum in Macarthur Street, East Melbourne.

An institution of the sort had long been campaigned for as a centre for geological research. But when the museum opened in 1910, the government justified the cost in terms of its economic – not scientific – benefits to the State.

The life of the Geological Museum was brief and embattled. In 1965, the building was demolished and its contents eventually moved to the Museum of Victoria in Russell Street. But, wrote the Mining and Geological Journal:

The Russell Street Museum will never have the power to summon up the legends of the Geological Survey. To the greats of the Survey the old building was more than a Museum – it was a kind of temple…

Today, the rocks and fossils carefully collected by geologists over the decades form part of the extensive reference collections maintained by Museum Victoria.

Page last updated: 02 Jun 2021